Come 5th January 2017, I’ll have made 9 months in Germany. Though I call Göttingen my home, I spend a considerable percentage of my time in Aachen – a city I’ll write about soon – or elsewhere, making Göttingen feel not completely familiar or home-like.

In October 2016, I moved from Kreuzbergring to Göttingen’s Innenstadt. The three months that have passed by in the new place – tumultuous with regard to noise, privacy and cleanliness – did one thing. It brought me closer to Göttingen. It is hard to ignore the fact that geographically, being stationed at the very centre of a flower not just lets you smell more but see more from an unexpected perspective. Imagine seeing from inside a flower. From its belly. From invisible visibility.I walk to the bus stop to take my bus. I have a routine check of what needs to be taken. I cross the road at the exact same point – in front of Crehaartiv. If there are vans or other interruptions to familiar views, I see through them, to the other side. I know if the mannequins have had a change of clothes. Even though we do not speak or smile, I walk past people I’ve walked past before. The manager at the Effes Imbiss does smile though. I walk into Esprit to get warmth, along with others who do the same while we wait for the bus. If not for the bus, I quickly course through the cobbled streets, past Fachwerk houses – past the one where Coleridge lived for four months in 1799, attending theology and natural history lectures at the University of Göttingen. He writes,

“by three month’s residence at Gottingen [sic] I shall have on paper at least all the materials… of a work…. I have planned… a Life of Lessing—& interweaved with it a true state of German Literature, in it’s rise & present state.—at Gottingen [sic] I will read [Lessing’s]… works regularly, according to the years in which they were written, & the controversies, religious & literary, which they occasioned.”

Every time I see his plaque outside the building in which he lived – above a clothing store named “White Stuff” – I’d wonder if I’d have a plaque. If I’d write so profusely as he did. If I’d live longer than I’d live. But I also know that Coleridge, prone to opium addiction, did not finish his Life on Lessing. I walk by in firmness – I remember everyday that which went unwritten in this very town, very close to where I live. I want to mumble that I won’t leave anything unwritten but Coleridge has also taught me to not make plans. Like this, the streets unwind.

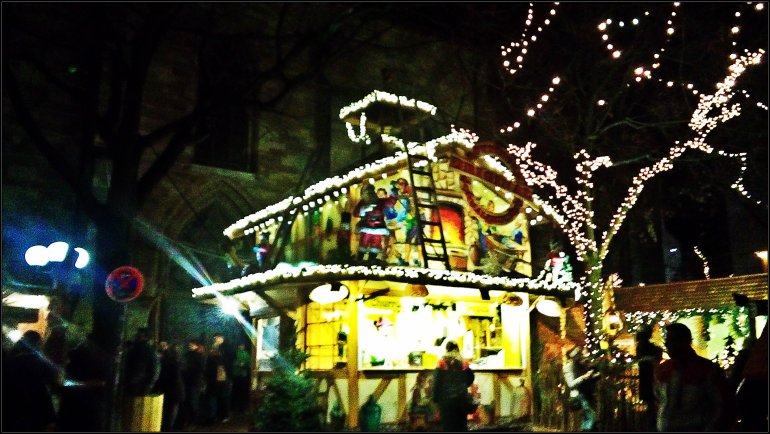

There’s the goose girl – Gänseliesel – and the antics that happen around her. There’s the Nabel, the belly button of this town where I always wish to sit at but never do. There are churches in front of which I don’t bow my head but raise it to trace the stretch of it, right up to the sky, which they pierce. By way of an unasked for friendship, Göttingen has come closer.But it was our brief tryst that began after the initiation of the Christmas market that “plaqued” me on the town’s walls and the town on my body’s. The stretch of shops that run down Johannisstraße, next to St. Johannis Kirche, are less crowded than those near the Gänseliesel. Here I usually sit on a tree trunk near a wooden bear frozen in bodily sprawl and a scream with a glass of Glüwein and a sausage. Or stand next to a wooden witch, not as tall as me but close. With Christmas around the corner, it always seemed right to think of the Christian conscience, of ideas of forgiveness and redemption and of Christianity itself.A man once told me that we postcolonials overdo Christianity and yes, in my postcolonial, Anglophilic blood and mind, there’s a strong affinity to Christianity. I’ve come to practise it in moderation and practise it in my own way but there’s no denying Christ in my life. I was taught a stringent dependence on Christ, on a Father in heaven. I was taught to capitalize the ‘F’ather – in all senses of the word. I was taught what sin was and how to stay away from it.

As much as it shaped my worldview – at first I knew of the world as one that started in Genesis and now I know it as a timeline involving Constantine, the Nicene’s Creed, St. Augustine bringing Christianity to England, Alfred the Great, early Christian literature in England, the rise of Rome, the decline of Rome, the fall of Rome, the continual crusades in the Holy Land, Luther, the rise of Protestantism, etc., – it also constricted my worldview.I don’t know the world if not by way of Christianity, a religion that has played its own difficult role in stirring conflict, in naming people with alternate beliefs as pagans, robbing conquered lands of their faith, removing sexuality from women, branding them as witches, removing the idea of a spiritual Holy Mother (not Mary), and effectively installing a patriarchal language which is today so deeply woven into not just the conscience of a Christian postcolonial but also in every other remotely religious Christian who has heard repeatedly that barren wombs are curses, women’s bodies are to be hidden under veils and their heads bowed down in sacred places where they cannot also raise questions. Christian scripture is still a tool of power and streamlines gender politics.Christianity taught generations and centuries and still does, that the world came from a “Father” who made us in “His” likeness.

By doing so, it denied that the first man came out of a womb – be it an ape’s or a homo erectus’. It denied the womb of a woman, it denied the womb’s power to create. It denied that the womb played a crucial role in the beginning of life, in the beginning of humankind. It taught the world that woman was created as a “helper”. It taught us that Eve was made from a rib in Adam’s body, effectively toppling the female womb. Effectively teaching women all around the world, throughout history that they are to hold a place in the world only in relation to a man, only as a product of a man’s agency to life; a by-product subject to an inferior position to those who were not “cursed” by way of being descendants of the first woman, the mother not of humankind, but of sin. It gave us Eve, a woman other women are taught to be ashamed of, the very oldest instance of portraying women as ones who lead men into sin, into deception. It called childbearing a “curse”, menstruation an “unclean” thing that required numerous washings, depravations and isolations. It told us that by way of being born, out of a womb, we are consumed by sin. It portrayed Mary as a “vessel”, her womb as a mere vessel, which was affected by the “Spirit of God” to bring forth the “Son of Man”, once again underplaying the power of the womb. It gave us a Man whose blood redeemed us, a Son of “Man” and not of woman. Even though it gave us the paradox of one God vs. His Triune manifestation, there was no Mother in the Trinity.

By possessing a scripture that is the first printed book in the history of printing and one which still holds a bestseller position, Christianity continues to reiterate its language of oppression, especially in postcolonial countries where it has become a tool of justification for the subjugation of women and their rights. It becomes a tool that propagates domesticity of women, femininity of women, and the invalidity of women when they remain unmarried or without giving birth. It has given us words of division even apart from these that affect women. It altered histories, it pushed some narratives to the fringes. I go on in this internal conflict with the sign of the Cross I have tattooed on my chest…Ruminations in December also involve the coming New Year. And sitting there, in the heart of Göttingen, in its pinching chill, I decided to resolve the clash between my Christian upbringing and my faith in the power of a universal Mother, my mother. The last day I sat there, I almost bellowed out her name from the depths of my own womb. Don’t mistake me, I do know that the word hysteria came from the word womb and branded all women to come as “hysterical”. But I do not want to make new words, I want to topple the existing ones. I want to reclaim everything that has been thrown at womankind. This year, and in the years to come, I will speak words that are allowing to women, kind and true to women.

There, in the centre of Göttingen, I chose to worship my Mother, her life-giving womb, as my Christ. My Christ is a woman and she sacrificed not just blood for me, she shed flesh too. There, I put an end to the father, to capitalizations, to venerations, to ideas of respect and forgiveness I was taught as a child, to hold up no matter what, and chose the mother.

(avrina)